Listen to this story [12 min]:

Susan Poulin—a writer and performer well known for her Maine life-coach persona Ida LeClair—loves to tell stories. In fact, she has often been called the funniest woman in Maine. Aside from performing and producing her own plays, Susan has written two books: The Sweet Life and Finding Your Inner Moose. Although Ida figures prominently in her life, Susan has also dedicated time and effort to researching her Franco-American heritage. This led her to write the play Pardon My French and also brought her to the Portsmouth TedTalk stage for the presentation: “Can You Find Your Identity Through a Heritage Language?” Throughout all of these explorations, she has found that some of the best material comes from her own family’s stories. Sometimes the best way to reconnect with your culture is simply to listen to a good story. Fortunately, Susan has decided to share one of hers. The following story features her grandfather George:

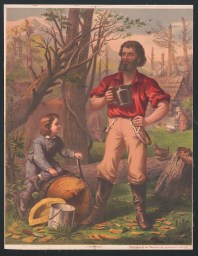

Photos courtesy of the Poulin Family

Susan: “My Grandfather, George Poulin, was a lumberjack for most of his life. My Dad told me that in the early 1920’s or late ‘teens, his father and a lot of lumberjacks used to go into the woods for the entire winter. They’d come back out in the spring, just before the ground thawed.”

The life of a lumberjack in those days was a hard one. A lumberman worked long, arduous hours in the harsh conditions of the north Maine woods. As soon as the ground froze in the late fall, lumberjacks would pack up their belongings and head for the woods, leaving family and friends behind. Working together in logging camps, crews of men would brave the winter weather to fell trees for the spring log drive. George was very much like other lumbermen of the time, except that he decided to bring his wife and their children with him into the woods.

Susan: “In the early years of their marriage, my grandmother, Georgiana, would go with my grandfather. They’d pack everything into a big, horse drawn sled, everything they’d need for the next three or four months and go. And they had two young children at the time: Ralph, who was a toddler, and a baby, Lillian. My grandmother would ride in the sled, on top of the supplies, with Lillian in her arms while my grandfather walked behind. There was too much on the sled for him to ride, too. He carried Ralph in one of those wicker knapsacks.”

Over the years George worked for a few different companies. He spent time with New Castle Lumber, but for most of his life he was employed by the Hollingsworth & Whitney Company. Although George’s cabin was small, he was fortunate to be able to provide a private space for his family. Lumber camps were not known to be the most hospitable of places—often the entire crew were lodged in a single building. George went out with the crew during the day while Georgiana remained at their cabin with the little ones.

Susan: “God, it must have been tough for my grandmother. She lived in a little cabin in the woods, with a dirt floor. Can you imagine? All winter long in a drafty cabin with two kids playing on the dirt floor. No medical care. No books to read. Hardly any other women to talk to. Day after day. Cooking on a wood stove. Melting snow to do laundry. Her only luxury was a square of wood that my Grandfather built her to put her rocking chair on.

Legend has it that my grandfather cut three cord of wood per day with a buck saw. Everyday. George knew how to pace himself, though. He would work for an hour, then sit down, smoke a cigarette and file his saw. An hour on, ten minutes off, all day long. He had a smooth, steady stroke, “like a good golf swing,” my father said.

Sometimes, in the evening, my Dad would see his father sitting there with eyes half closed. He’d ask him what he was thinking, and George would say, “L’arbre demain. Y’est pas bon. J’pense à comment j’vas l’abattre.” Bad tree tomorrow. I’m thinking about how I’m going to drop it.”

In 1918, with the birth of their third child, followed by their fourth in late 1920, Georgianna no longer accompanied George into the woods. Both Georgiana and George had their hands full, and the 1920s brought many other changes as well. With the passing of the 18th Amendment and the Volstead Act, the United States Congress forbade the transportation, manufacture, and distribution of alcohol. Though Maine was now dry, its next door neighbor Quebec was not.

There were, of course, many ways to evade prohibition laws—speakeasies sprouted up quickly in an effort to meet the demand for liquor—but those establishments near the international border were uniquely situated. Many business-minded people found convenient loopholes, such as building and utilizing “line houses.” These “line-houses” straddled the international boundary “line.” People might be subject to prohibition laws as they entered the house, but by the time they had walked to the bar located on the other side of the building, they would find that they could safely enjoy a drink on the Canadian side. Loopholes like these spurred two of the Poulin boys to try their hand at the liquor business.

Susan: “During prohibition, George’s older brother Ernest convinced him to quit lumbering and open a bar on the Canadian line. Despite my grandmother’s protestations, he agreed. What he and Ernest did was go up to the border, fifteen miles north of Jackman. Once they found the line, they built the bar on the Canadian side and the house on the U.S. side. That way they could sell liquor to Americans during Prohibition without smuggling. They never bought the land, though. They just claimed it as their own. As sketchy as it sounds, George moved the whole family up there.”

The borderline in northern Maine during those times was much more fluid than it is today. The U.S. Border Patrol was established in 1924, but it had its hands full trying to enforce both prohibition laws as well as immigration. The Maine-Canadian Border is over 600 miles long, so keeping tabs on all the untracked land was difficult. George and Ernest were able to proceed with their venture with little push-back. Technically, since they weren’t providing alcohol on the American side, the only infractions involved claiming unpurchased land and encouraging a steady flow of undocumented border crossings.

Susan: “I have an old photograph taken around 1931 at the line post between Maine and Canada. There are five men in it. The ones on the Canadian side have booze and the ones in the U.S. have guns. And they’re pretending to stick up the ones in Canada and take their liquor.

What makes this photo so precious to our family is that my father’s father, George, is one of the guys on the Canadian side (he’s the tallest one) and my mother’s father, Adelard DeBlois (anglicized to “Blue”) is one of the guys on the American side (he’s the one with the fedora). See, Blue was a bouncer at George’s bar. So here are both of my grandfathers in one photograph, before my parents were even conceived. My father would arrive two years later, and spend the first six years of his life living half in Canada and half in Maine, crossing the line daily.

Poor George was such a bad businessman, though, giving away drinks, inviting acquaintances to stay for dinner. My grandmother was left with the unenviable task of stretching out the food to accommodate an extra mouth or two, sometimes short-changing her children and herself. Was George soft-hearted? Did he want to be the big guy on campus? Maybe it was a combination of both. At any rate, it didn’t work out, and eventually, he went back to being a lumberjack. George will probably go down in Jackman history as one of the few people who actually lost money selling booze during Prohibition!”

George’s bartending days were over. He returned to the woods after Prohibition ended. He spent his winters cutting down trees, and in the spring he continued to help with the log drives. In 1933, George and Georgiana had their sixth and final child Patrick, Susan’s father. The family stayed relatively close to the Canadian Border, traveling across it often.

For the rest of his days, George did what he was good at; he worked timber with a saw. Yet over time the industry changed, and the advance of logging machinery made George uncomfortable. Eventually, it pushed him into retirement.

Susan: “He remained a lumberjack for most of his working life. The game changer for George was mechanization. Those chainsaws scared the bejesus out of him.

Whenever I pass the Kennebec River, I remember how it used to look when I was a kid, chuck full of logs during the drive. And I think of George. I can almost see him in his prime, dressed in his red flannel shirt, wool pants and spiked boots standing on the shore. With a sparkle in his sky blue eyes, he smiles, winks and turns toward the water. Then he sets off. And even though some of the bark has rubbed off the logs from all the jostling, exposing the yellow wood, slick with sap, George walks effortlessly to the other shore.”

Throughout his life, George proved that he was not only surefooted on slippery logs, but he was also not afraid to walk the tipsy line of legality, as long as family was involved. He wore multiple hats during his day: lumberman, barman, husband, father, and grandfather. He lived for his profession, one that has been steeped in Maine tradition and passed on through numerous tales and stories. Lucky for us, George had a few of his own to tell.

Special Thanks

This story was produced by Rhumb Line Maps and the University of Maine’s Franco-American Program in May of 2021. Special thanks, first and foremost, to Susan Poulin and her family for their story. Special thanks, also, to the Bicentennial Grant that made this production possible.

To see more of Susan follow the link here and to learn more about Ida LeClair click here.

Credits

Writers — Susan Poulin & Emily Meader

Editors — Catherine Jewitt & Ben Meader

Audio Editors — Ben Meader & John Meader.

Photo Credits — Poulin Family, Library of Congress.

Audio Credits — Susan Poulin & Ben Meader

Further Reading

—On Prohibition

Bauer, Words by Nicole Ziza, et al. “Prohibition Examined: Chapter II.” Life & Thyme, 28 July 2018, lifeandthyme.com/drink/beer-wine/prohibition-examined-chapter-ii/.

Okrent, Daniel. “Prohibition: Speakeasies, Loopholes And Politics.” NPR, NPR, 10 June 2011, http://www.npr.org/2011/06/10/137077599/prohibition-speakeasies-loopholes-and-politics.

United States. National Archives and Records Administration. (1986). Prohibition: the 18th Amendment, the Volstead Act, the 21st Amendment. Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uva.x004095569&view=1up&seq=1

—On Logging

“King of the Log Drives: The New England Riverman.” New England Historical Society, 17 Apr. 2020, www.newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/king-log-drives-new-england-riverman/.

Owner, WSD. “A History of Maine Logging.” Wood Splitters Direct, Wood Splitters Direct, 11 Feb. 2020, www.woodsplitterdirect.com/blogs/wsd/a-history-of-maine-logging.

—On Maine’s Border

“Houlton Sector Maine.” U.S. Customs and Border Protection, www.cbp.gov/border-security/along-us-borders/border-patrol-sectors/houlton-sector-maine.

Leave a Reply to Jewel B DavisCancel reply